A New Psychology For Existentially Complex Times

Psychology isn't just about all the feels. It's a vital part of effective work caring for, repairing and healing our world, regardless of your sector or role.

Only a few decades ago, worries about our planet’s various existential crises were discussed only in certain pockets of society: by seemingly alarmist scientists and tree-hugging hippie activists, on daises at the United Nations and in somber TV commercials for various nonprofits. These occasional yet inconsistent alarm bells—about climate change, nuclear war, genocide, poverty, and a host of other ills—all emitted a clear signal: If we don’t do something, we’re headed for trouble.

Fast forward to today, and we are no longer heading for trouble—we’re in trouble. From fires, floods, and hurricanes to food shortages, inflation, and intractable global conflicts, the bad news has breached the borders of everyday life. Events over the past several years have created an unprecedented confluence of wake-up calls that can’t be ignored. And now, we all know it.

As a result, humans are living with unprecedented levels of anxiety and fear (reflected in the soaring increase of antidepressant use, by almost 40 percent globally over the past five years, alongside a reported burnout rate of almost 50 percent among mental health professionals, and suicide rates have climbed for the last 20 years in the US).

It would seem that responses to the cascade of big, complex issues is apathy and inaction. Or if not inaction, showy but empty pledges, commitments and promises.

Beleaguered, tired activists, intrapreneurs, leaders and hand-wringing journalists keep telling us the same thing: that by and large, apparently people simply don’t care enough to ward off even the gravest and most devastating of global upheavals.

Many of us believe this, and think the answer is to get louder—keep connecting the dots between extreme weather events and tragedies such as the recent devastation in the US Southeast and North Carolina—with the thinking: if it gets bad enough, people will finally get it. We have to share more, disrupt more, and educate more, or else people will never care enough about our wellbeing or the fate of life on Earth.

Or we think we have to only come up with more compelling stories, create more wonder and awe, and somehow make people care.

So much of our action stems from a fundamental, underlying belief in apathy.

However, the idea that our failure to respond to our global polycrisis with decisive and revolutionary action is due to a mass affliction of apathy, I maintain, is a myth—and one that has us heading in exactly the wrong direction.

What if I were to suggest that the truth is that everyone cares, but are generally stalled out, often unknowingly, with anxieties, ambivalence, overwhelm, etc.? That we actually need help with knowing how to get our minds around these crises that exceed normalcy?

If this is true, this is very good news for everyone in the business of making society better. I won’t accept that the only effective catalyst for massive change, and seeing the light, is a natural disaster striking. Neither should you.

But we’ve been missing an essential tool from our toolbox.

To change the world, we must rethink our relationship to change itself.

I began studying why people engage or not– what is referred to as apathy—in the late 1980s. Through individual interviews, large-scale surveys, and consultation for some of the world’s most influential companies, universities, nonprofits, and government agencies, I learned that the conversation around apathy is missing critical information that connects the dots between existential threats and scientific research in the areas of psychology, neuroscience, and trauma.

How does this help us as we go about the business of creating transformational change in our world, in our communities, networks, businesses, organizations, and policies?

In the way Bessel van der Kolk helped us reframe personal and collective trauma in The Body Keeps the Score, we need a new psychology for our times that can address the complexities of existential planetary issues, guiding us to unlock our capacity to face, contemplate, and create seismic behavioral change—individually and collectively.

By diving into what we desire, are afraid to lose, and where we short circuit our own care, we get at what it takes to ‘guide’ each other into new ways of living. This kind of approach will help us access the art of relational approaches to care. This has huge impacts for our approaches to change making, leadership, and how we show up in our daily lives. As people who care, and know how to unlock this care in others. Instead of defaulting to yelling, telling or selling, I offer a new baseline.

I believe a basic understanding of guiding psychological principles is the most essential tool for every leader in this century to obtain. This is the key to helping people remember that they care—so that they will enact change with or without you.

It's clear that yelling, selling, and telling has not, and likely will not, deliver these results. We are left with the monumental challenge of becoming guides. That is where I place my bets, and invest my energies in working with organizations, teams, leaders and communities.

What do you think?

The Three A’s—How to Unlock Care

Over the years I’ve been developing tools and resources to help people apply these psychological principles. Many people working on big complex social issues, from dam removal to deforestation and species loss, often overlook practices from clinical psychology, with the assumption that it’s only for individuals and specific behavior changes. This is not correct—it just requires some innovation and creativity to translate from clinical work to social systemic work. (Ideally done in partnership with clinically trained people who would love to be asked!)

I refer to these principles broadly as “guiding,” as I’m inspired by research in Motivational Interviewing (MI)–the most evidence-based approach to behavior change. In MI, they refer to the difference between “guiding” and “righting”—and my life has never been the same (more on guiding versus righting, and more, to come!). As it happens, MI is a powerful distillation of many psychological principles we can be incorporating into our work. Starting now.

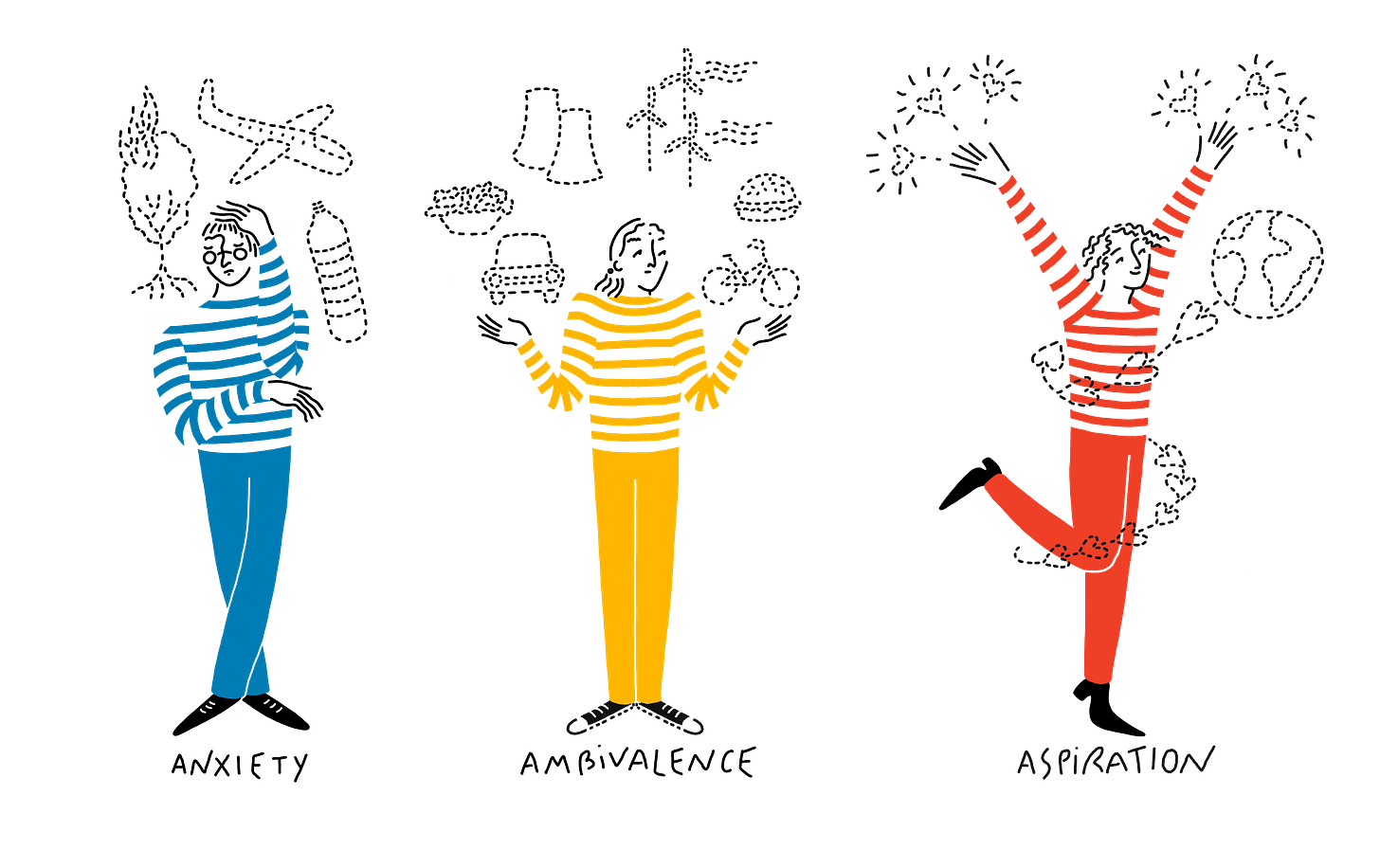

I want to share one simple framework that I call the Three A’s with you. We will refer to this often as it’s foundational to everything, and I’ve seen firsthand how it can totally change the outcomes of work at all levels. The A’s are Anxiety, Ambivalence, and Aspiration.

The Three A’s reflect how desires to do something about the complex problems we face in our world can get tangled up, diverted, blocked or submerged. When we can tune in and understand these As in ourselves and those we seek to engage, work with, connect with— it’s game changing. The key is to practice attuning, and naming these A’s.

A Story Of Three A’s

I created this concept when teaching at Portland State University ten years ago. I had a student, Amanda, in a class on the psychology of climate change. She came into my office one day, flustered and upset. She had just seen a book called 100 Places to See Before They Disappear. She started recounting the moment of “I can’t believe there is a book about places disappearing. That is crazy AF.” It was that surreal confrontation many of us have had, with the unthinkable. She felt deeply anxious and worried. Then, she was seized with a desire to go fly around the world, and see these places. Immediately she realized by jet-setting she’d be contributing to the very problem creating this crisis: an ambivalent and aspirational experience. As she told me this cycle of feelings that lasted only seconds, I realized—this is what so many of us are experiencing. And yet we didn’t have words for it. Thus became the Three As.

The Three A’s help us slow down to understand that for many people, whether it’s investors, board members, shareholders, teachers, innovators, you name it, we experience a tangle of these feelings when confronted with responsibility for varying systemic threats and challenges. We have different parts of ourselves. Some want to do something, other parts want to hide in fear. Other parts are feeling torn and conflicted. And yes, other parts deeply aspire for a different future, and the ability to do something in service of healing, repair, and making things better. When we aren’t able to act on those aspirations, while also being faced with anxieties and ambivalence, we’re left with a messy entanglement because of our innate care - we make a grave mistake when we name it as apathy.

We Deserve More Options

When we listen, pay attention and name these As, things change. Our defenses can calm. We can become more open. Most importantly we feel heard, seen and understood. We can actually learn and receive new information more effectively when we are attuned with. We feel less alone, that our experience makes sense. Our parts can have space to be voiced, and therefore, potentially change and evolve. We can access our reparative capacities much more.

Deep, personal change doesn’t require billions of dollars, state-of-the-art technology, or crises sparked by disasters. It requires us to be more actively involved in the difficult work of being human.

There is more to say on this, but for now practice tuning into your own Three As, and that of others. If you are designing a campaign, meeting or strategy, consider these Three A’s. If you are collecting information and insights, make sure to include the As.

Thank you for being on this journey with me, and I am glad you are here.

Renée

This idea of inner work as solo work is a neoliberal lie and a big part of what contributes to persistent dis-ease. As many people in 12 step programs say, "Don't go into your head alone; it's a bad neighborhood!" Therapeutic community is the way.

Hello Renee

I resonate with your diagnosis that apathy is not at the root of so much inaction. I look forward to more distillation of how the three A's, like Motivational Interviewing, can be used as a technique to connect, engage and inspire.